Childcare Environments

Men in Childcare & the Implications of Gender Bias in Early Years Settings

Having seen the meagre proportion of men in childcare in New Zealand’s early childhood workforce slide from just over 2% in 1992 to less than 1% by 2005, Dr Sarah Farquhar and many other observers felt it was time to ‘draw attention to the need to involve men in greater numbers in the work of childcare’. The title of her study ‘Men at Work: Sexism in Early Childhood Education’ (2006) leaves little room to misconstrue her chief concern, and the paper argues that what she considers to be one of the primary causes of this gender imbalance – the sector’s veiled sexism and complacent attitudes – is rarely voiced as an issue. Adopting a forthright stance, Farquhar contends that:

‘Society has moved on, men are more actively engaged in caring for their children; yet the early childhood workforce seems stuck in the 1970s family model’ (Farquhar, 2006)

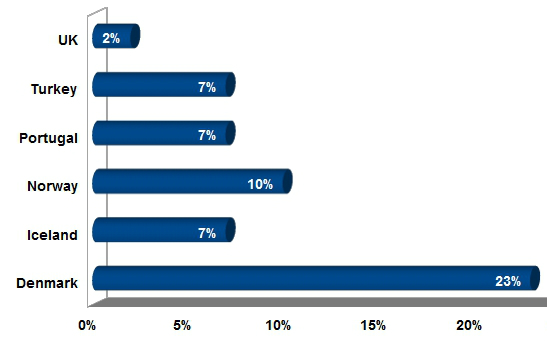

As Mistry and Sood (2013) and others have noted, under-representation of males in Early Years settings occurs on a similar scale in the UK, and a glance at Figure 1.1 shows that even those European countries which are presently forging ahead are a long way from achieving anything approaching an equitable balance.

Figure 1.1 Proportion of men employed in childcare sector (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice/Eurostat, 2014)

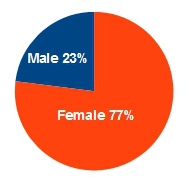

Though not on the same scale as the childcare workforce, other UK caring professions undoubtedly experience a similar pattern of recruitment. For instance, even with acknowledged media support (from sources such as the BBC’s Casualty series which depicts male nurse roles) NHS figures (see Figure 1.2 below) still show male nurses account for less than a quarter of the total NHS workforce.

Figure 1.2 Proportion of male nurses employed within the NHS (General and Personal Medical Services in England 2005–2015)

Gender imbalance – what’s the problem?

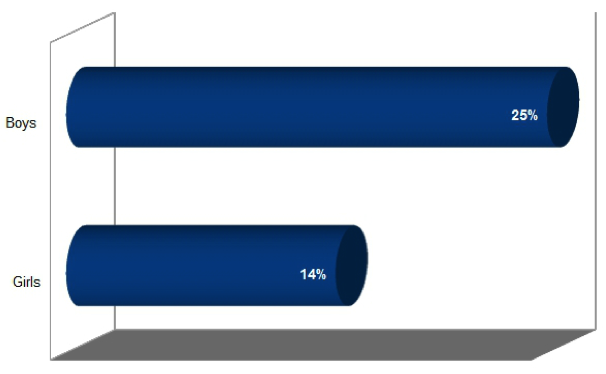

Though accepting its contribution to gender politics, many reading Farquhar’s robust critique of New Zealand’s childcare as a ‘site of feminist activism … promoted by women, used by women, and worked in by women’ may well wonder whether this statistical analysis has any broader implications which might justify such censure. And in this connection, it may well be worth taking a critical look at UK data such as the Save the Children commissioned report ‘The Lost Boys: How boys are falling behind in their early years’ (Read, 2016). As illustrated in Figure 1.3, this document highlights the current early years gender gap with ‘boys nearly twice as likely to fall behind as girls by the time they start school’.

Figure 1.3 Percentage of UK children assessed as falling below the expected standard in early language and communication – results split by gender (Inspired by Read, 2016)

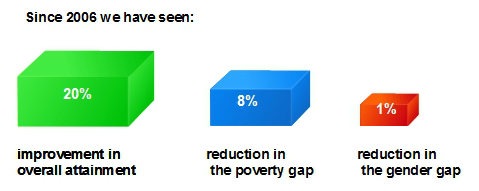

To underline the relevance of this report to the gender bias debate, it will be helpful to set out three further progress indicators which Save the Children highlight from the same report data (see Figure 1.4):

Figure 1.4 Save the Children’s ‘Lost Boys’ report in numbers (Inspired by Read, 2016)

These figures confirm that the gender gap in attainment has shown negligible improvement over the last decade. Though such an issue is undoubtedly a multi-faceted problem, when it comes to investigating possible causes, neither the report itself, nor government ministers, nor the broader childcare sector, consider the inherent gender bias of a female-dominated workforce even worthy of mention. In the light of the wider and well-publicised debate about boys’ attainment, such oversight at the very least implies a staggering 360-degree complacency, and some have even expressed concerns that ‘a “quiet conspiracy” is keeping men out of childcare jobs’. (Paton, 2009)

Who’s truly in loco parentis?

Childcare professionals are aware their job role involves acting ‘in place of the parent’. However, despite Farquhar’s observation that society itself has moved on in terms of male involvement, the childcare sector seems happy to act as if their brief amounts to nothing more than ‘an extension of the role of women as mothers’ (Farquhar, 2006).

Other researchers, such as Bilton (2010), have similarly criticised the attitudes of adult childcare professionals on gender grounds, mentioning female early years staff who are ‘keener to be involved in sedentary activities, which usually take place indoors’ and who therefore contribute ‘minimal supervision’ outdoors and use more ‘negative controls’ (‘Don’t do that’) in connection with boys’ play. Elsewhere, Frederickson and Cline (2009) have cited several gender studies which show that, when they witness events where the gender of the child participants is masked, (female) teachers and care staff are predominantly inclined to attribute disruptive, aggressive behaviours to boys and compliant, affectionate behaviour to girls.

Further studies outline some of the many advantages and attributes male practitioners can provide for younger children. Brandth and Kvande, for instance, cite that:

‘… men are believed to offer a different set of skills, for example, playing outdoors, allowing children to be independent, and being more friendly with children.’ (Brandth and Kvande, 1998)

and the Children’s Workforce Development Council (CWDC) report mentions that ‘… 37 per cent of parents believe male practitioners will set boys a good example, while a quarter say they believe boys will behave better with a man.’ (CWDC, 2009)

Looking more broadly, research on boys achievement by Nobel et al. (2001) finds a pre-school education system, where many believe women do a perfectly good job, ‘seems to place a greater value on visual and auditory styles rather than the kinaesthetic styles which boys seem to favour in their early years’. (Solly, 2015)

Men’s work?

Devarakonda comments that ‘early childhood education remains one of the most gender-skewed of all occupations’ (Devarakonda, 2013), and studies documenting the views of male childcare workers reveal some familiar career barriers which inevitably contribute to this situation:

‘… a common perception is that men who choose to work with young children are often assumed to be “either homosexuals, paedophiles or principals in training”’ (Mistry and Sood, 2013)

‘Men who enter paid childcare work are often thought of as men who are not ‘real’ men or gay … In contrast, the sexuality of women in childcare teaching does not seem to matter. Lesbian teachers are not viewed as unsuitable candidates for working with young children.’ (Farquhar, 2006)

‘… it has caused some concerns over basic policies – things like parents questioning whether men will be allowed to change their child’s nappy … [however,] my workplace is very supportive of men … parents know that men work here and they are doing exactly the same job as the women. Our policy on nappy changing is that no nursery teacher, male or female, should do it alone without another teacher present.’ (Clensy, 2016).

EYFS Developmental Milestones – Download Free eBook

Those few men prepared to look at a career in childcare – and statistics confirm most do not – thus face an unpleasant cocktail of challenges: a self-satisfied sector promoting ‘jobs for the girls and the occasional boy’ (May, 2001); a complacent, laissez-faire political climate; and an ambivalent society which actively espouses progressive, gender-balanced caring, yet is still fickle enough to sign up to the odd, tabloid-inspired witch-hunt.

Farquhar again is uncompromisingly scathing in her condemnation:

‘The argument reversed – that men are doing a perfectly good job as politicians, as doctors, or in any other occupation so women should not be included in any great number – is not politically or socially acceptable. The belief that women are doing a good job as early childhood teachers should not be accepted as a reason for keeping the door shut on male entry to the early childhood profession.’ (Farquhar, 2006)

Meanwhile, young boys continue to experience what some believe to be a somewhat outdated early years education matriarchy which, we are told, is much at odds with the progressive, gender-balanced parenting practised in many nuclear families. Whilst this mismatch alone is cause for concern, the further restrictions this arrangement imposes upon the developmental prospects of male children from single-parent and other same-sex backgrounds which lack a significant male role model acting as a father figure are even more regrettable. Research from the Children’s Workforce Development Council (CWDC) confirms the extent of the deprivation experienced by this group:

‘… 36 per cent of children had fewer than six hours per week of contact with a male and 17 per cent had fewer than two hours per week.’ (CWDC, 2009)

So where do we go from here?

Whilst gender-aligned statistics continue to map the effects on young boys, those who are best placed to improve the situation – government and the childcare sector – seem afflicted by a self-serving inertia which appears to do little more than pay lip service to any serious initiative which might redress the current and inexcusable under-representation of male childcare workers.

As regards gender imbalance, the UK childcare sector is clearly not where it would want to be, yet appears to have no coherent future-oriented strategy in place. It would be at least instructive to hear something concrete from those who seriously believe otherwise.

References

You must be logged in to post a comment Login