Child Development

Playworker: The Adult Role in Outdoor Play and Learning

“Play is not an easy game.”

― Helen Bilton, author and Associate Professor, University of Reading

For many, the idea of playwork suggests little more than enlightened childminding, but Waller (2011) notes that, in reality, adults have a crucial role to play in enhancing the quality of children’s outdoor experiences. This view is endorsed in the EYFS documentation which insists that:

‘The attitude and behaviour of adults outdoors has a profound impact on what happens there and on children’s learning. It is therefore vital that children have the support of attentive and engaged adults who are enthusiastic about the outdoors and understand the importance of outdoor learning.’ (DCSF, 2008)

What makes an adult presence essential?

To be truly effective, outdoor play and learning for pre-school children must be given the same priority and resources as indoor learning. If this is to be achieved, then staff must also approach outdoor activities with the same professionalism as they routinely bring to the indoor classroom. Anything less, Bilton warns, is simply unacceptable, reminding us that ‘viewing outdoor play as [the time] when staff have a break is about the needs of staff, not the children.’ (Bilton, 2010)

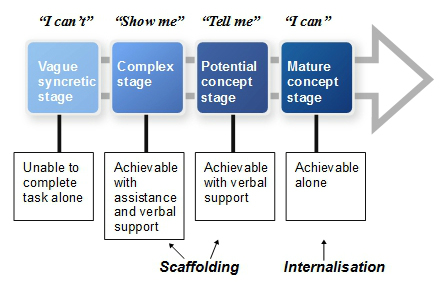

If meaningful learning and development is to take place outdoors, Vygotsky’s model of social learning suggests that the quality, frequency and timing of interactions between children and facilitating adults are central to the development of higher order functioning. Diagram 6.1 conceptualises this process as a child’s journey towards functional competence on any particular task. Among many important developmental features which occur, the principal change which is promoted during such child/adult interaction is the gradual movement towards the interdependence of thought and action. Once achieved, this higher order functioning equips the child with a vital tool for a lifetime of learning. Practitioners should particularly note that the skilful deployment of language plays a prominent role at each phase, indeed the bulk of adult ‘scaffolding’ will take this form.

Figure 6.1 Vygotsky’s phases of social learning (Inspired by Vygotsky, 1978)

Commenting on the acquisition of higher order skills, Bilton describes the process as being:

‘… about the development of intellectual self-control and leads to the development of thinking which is characteristic of logic, perseverance and concentrated thought.’ (Bilton, 2010)

Recent findings by Richland and Burchinal support Bilton’s assertions and indicate that ‘teachers may be able to help encourage development of executive function by having youngsters help plan activities, learn to stop, think, and then take action, or engage in pretend play,’ (Richland and Burchinal, 2013)

Outlining staff roles

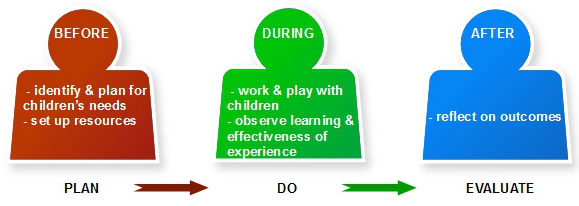

If children’s outdoor experiences are to consistently contribute to their learning and development, then staff must adopt professional roles and practices which positively contribute to this aim. In terms of daily routines and outdoor activities, Figure 6.2 outlines the actions staff will regularly undertake to effectively prepare, execute and develop any programme of outdoor play and learning.

Figure 6.2 Staff roles in outdoor play & learning (Inspired by Bilton, 2010)

Whilst the need for pre-planning and organisation is obvious and cannot be avoided, careful observation of what children do and say during the activity is an essential professional discipline which informs both present practice and future planning. Solly suggests that observation feedback provides essential data on child development which enables practitioners to answer questions such as:

- ‘What do we need to change, extend or develop to build and/or challenge this child’s interests, needs, development, skills, knowledge and understanding?

- How can we ensure that this child and others access the learning opportunities provided through challenging play?’ (Solly, 2015)

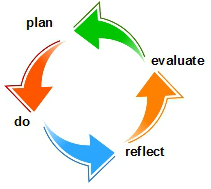

Taking Bilton’s model a stage further, like all education professionals, staff will find their most effective practice will be achieved if they can operate as reflective practitioners. This four-phase mode of critical reflection which continuously informs the delivery of learning programmes is presented in diagram form below:

Figure 6.3 The cycle of reflective practice

Learning interventions

Whilst it is true that the majority of outdoor play is frequently child-led, this should never imply that adults are merely passive observers. In fact, the essence of skilful practice dictates that adults will at times function interactively or become collaborators, and be fully prepared to interpret and facilitate play situations where such interventions will benefit the child. These kinds of adjustment or refinement will always require careful judgement as regards the timing and extent of adult prompts, and should never become the primary mode of interaction. However, when sensitively executed, these forms of scaffolding have the potential to advance young children’s thinking and learning.

Supporting outdoor play

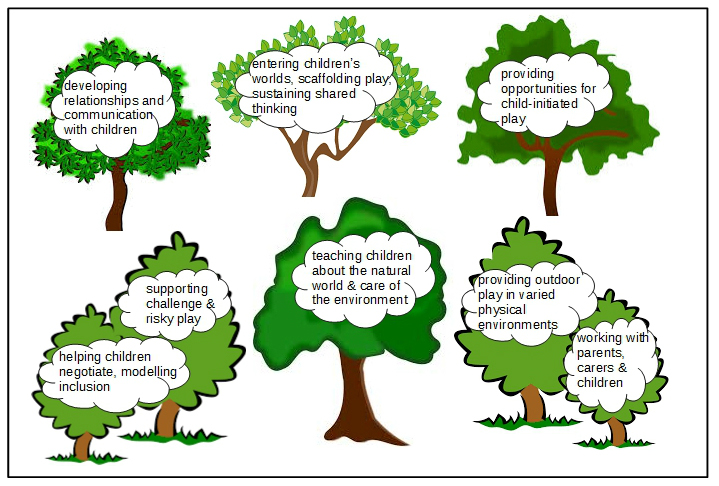

The richness of the outdoor environment generates endless opportunities for learning, and the adult supportive role which unlocks this potential must thus take a variety of forms. Waller, for example, believes staff are often called upon to act as ‘reflective practitioners, thinkers, researchers and co-constructors of knowledge with children.’ (Waller, 2007). His taxonomy of key supporting functions which adults will encounter in childcare settings is outlined in Figure 6.4, and gives a flavour of the diverse range of skills a childcare professional is expected to acquire and regularly deploy.

Figure 6.4 Supporting children’s outdoor play & learning (Inspired by Waller, 2011)

Playworker qualities

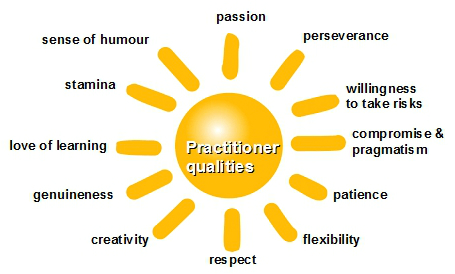

In addition to a range of sector-related skills, a successful adult playworker needs a rounded disposition and a broad range of personal qualities (summarised in Figure 6.5 ). Whilst some of these traits identified by Solly (2015), such as flexibility, compromise and pragmatism, can be acquired and developed through practice and experience, other qualities are perhaps more innate characteristics. This latter category would perhaps be more likely to apply to qualities such creativity, patience and perseverance.

Defining The Outdoor Classroom – Download Free eBook

As is the case with many personal attributes listed as ‘career essentials’, there is a natural tendency to feel intimidated by the scope of the theoretical requirement. However, the practical reality is that it is profoundly more important to understand and recognise how these qualities contribute to a quality learning experience for young children. For reflective practitioners aware of this perspective, the refinement of one’s personal profile then becomes a career matter addressed via continuing professional development.

Bilton summarises how many of these practitioner qualities might combine and interact when she describes the typical adult role as:

‘… keeping a watchful eye, observing, scanning, anticipating problems, knowing who may need help, but at the same time giving children a degree of privacy.’ (Bilton, 2002).

Figure 6.5 Practitioner qualities (Inspired by Solly, 2015)

Gender-influenced adult behaviour

It has often been noted that early years provision is a female-dominated environment. Whilst this may be factually so, it should never be the case that this introduces a gender bias into the types of experience girls and boys are allowed to access. Bilton (2010) has observed that the outdoors is ‘not necessarily a natural environment for many [female staff]’ who are often ‘keener to be involved in sedentary activities, which usually take place indoors’. Nevertheless, many outdoor activities do naturally have a DIY element, and involve games or heavy, active work.

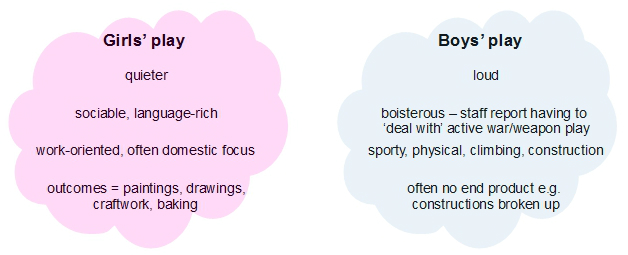

Broadening this discussion further, there are certain distinctive tendencies which research has generally associated with the play activities of girls and boys – as outlined in Figure 6.6 below:

Figure 6.6 Distinctive features of girls’ and boys’ play

Further research also suggests that the following trends were frequently observed when staff worked with children outdoors:

- less time was spent talking with children

- tasks generally had a lower cognitive content

- more negative statements occurred (e.g. don’t do that)

- levels of monitoring were lower

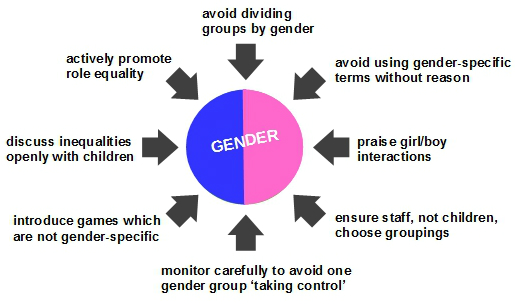

This evidence seems to imply that staff need to be aware that their own preferences for indoor/outdoor work and activities can exert a detrimental influence if they are unconsciously allowed to dominate curriculum planning. Thorne has listed eight measures which staff can employ to help counteract the development of such tendencies by modelling gender-neutral or remedial behaviours, as indicated in Figure 6.7 below:

Figure 6.7 Measures to limit gender bias during outdoor play (Inspired by Thorne, 2002)

Summing up the core elements of a balanced approach, Bilton comments:

‘… differences between people have to be recognised; men and women are different, they do take on different roles, but no one is better than another by virtue of gender.’ (Bilton, 2010)

The adult practitioner’s ultimate goal in supporting children’s play is the subtle and sophisticated development of child-initiated ‘mature play’ (Elkonin, 2005a). Far from being an adult attempt to hijack children’s play, or the mere insertion of ‘playful’ elements designed to disguise the advent of formal learning, mature play, according to Zaporozhets (a student of Vygotsky), is a dedicated process of enhancement:

‘Optimal educational opportunities for a young child to reach his or her potential and to develop in a harmonious fashion are not created by accelerated ultra-early instruction aimed at shortening the childhood period—that would prematurely turn a toddler into a pre-schooler and a pre-schooler into a first-grader. What is needed is just the opposite—expansion and enrichment of the content in the activities that are uniquely “pre-school”: from play to painting to interactions with peers and adults.’ (Zaporozhets, 1986).

References

You must be logged in to post a comment Login