SEN In Early Years

Special Educational Needs in Early Years

As elsewhere in the wider community, some children in an early years setting may have special needs associated with a physical or medical condition. Often, this will have no influence on their ability to learn, but if learning capacity should be impaired, then their education may fall within the remit of Special Educational Needs (SEN) legislation. Institutional responsibility for this sometimes poorly understood educational provision is usually delegated to a specific member of staff, whilst other colleagues, and most parents, may find its complex web of regulations bewildering and even a little intimidating. For those wishing to learn more, this article outlines the evolution of the SEN concept which informs the education of many of our children.

Out of the Shadows

As in many cultures, we have inherited our notions of disability and impairment from a medieval world of demons and punishment. Meighan1 believes this mix of history and myth is still echoed in our contemporary society via the ‘negative labelling of “special” or “handicapped” children’ often ‘cloistered away from the general public’. Centuries later, scientists from the Age of Enlightenment developed a more-informed understanding of many disabling conditions as medical science began to discover a range of relieving treatments and cures. Unfortunately, these celebrated advances were also accompanied by a tendency to map and classify the attributes of human ‘normality’, immediately stigmatising anyone unable to meet such specifications as ‘abnormal’. Even more importantly, the outcome of such pronouncements often condemned individuals to a dismal life of exclusion and segregation – a practice which was still relatively common during much of the 20th century.

Special Educational Needs in Legislation

In the world of education, the SEN journey from harsh segregation to integration and enlightened inclusion can be tracked via legislative reforms.

Though the first UK special school dates from 1791, and the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act made special provision for children with disabilities, the Education Act (1944) was the first significant attempt to sketch a Special Needs landscape. This legislation introduced 11 classes of ‘disability of mind or body’ and endorsed separate special schools, whilst still declaring some children ‘educationally sub-normal’, or even ‘ineducable’.

Prompted by the groundbreaking Warnock report of 1978, the 1981 Education Act switched the focus from group classification to individual needs, and established the principle that, wherever possible, children with special educational needs belonged in mainstream education. Then, under the Education Act (1996), every local education authority (LEA) was obligated to inform parents of children with SEN about the local services available.

More radical change in England was effected through The Children Act (2004) which advocated inter-agency working and, for example, ensured the integration of SEN provision in school- and early years settings. Whole-system reform became a priority, and transformative frameworks such as ‘Every Child Matters’ (DfES, 2004) detailed what the changes should look like. The consolidating Equality Act of 2010 then outlawed discrimination against any child with SEN – for example, making it unlawful for any early years setting to operate a discriminatory admissions policy.

The latest SEN reforms are incorporated within the 2014 Children and Families Act, which places children and parents at the core of the system: Inclusive Education Health and Care (EHC) Plans replace SEN Statements, the LEA and all other agencies must work collaboratively, early identification is paramount, and seamless SEN support is promoted from birth to age 25.

This statutory framework can be read as a welcome streamlining and development of contemporary SEN best practice. However, it will be clear to early years practitioners that the renewed emphasis on prompt action and multi-agency data sharing, plus the explicit reference to access and entitlement from birth, now places childcare professionals at the forefront of the process of detection and assessment of possible educational disadvantage, which may often trigger SEN intervention.

The Disability Debate

Those likely to encounter SEN contexts should be aware the concept of disability can be controversial. Early assumptions (and some SEN legislation), as Devarakonda2 and others have observed, cast disability as:

‘… a problem that was within the individual and had to be fixed or cured by therapy or special treatment. The focus was on the impairment of the child.’

This view is described as the ‘medical model’ and opponents argue it seeks to adapt those with a disability to conform to the needs of a non-disabled world, and prescribes segregation for those who cannot comply.

In contrast, a more recent view known as the ‘social model’ considers that, even though impairment and chronic illness are a difficult reality:

‘Disablement is the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical and social barriers.’3

Frederickson and Cline4 note that, according to this perspective, ‘wheelchair users would not be seen as people with a mobility problem. Instead they would be seen as people whose mobility is often hampered by inappropriate building design.’

You can read more about Disability and Inclusion here.

Each view has its partisan adherents, but most modern legislation and educational best practice adopts an ‘interactional’ perspective which views SEN needs as ‘a complex interaction between the child’s strengths and weaknesses, the level of support available, and the appropriateness of the education … provided.’

Integration or Inclusion?

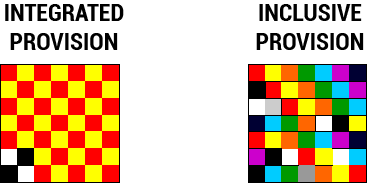

Modern SEN legislation anticipates the majority of all children with SEN will be educated in mainstream settings. Nevertheless, as Thomas & Loxley5 and many others insist, ‘inclusion is about more than merely the integration of children from special schools into mainstream school’. Ainscow6 characterises this essential difference by asserting that, with institutional integration, limited arrangements are made for a few children with SEN without changing much else, whereas inclusion implies more radical change and restructuring, thereby enabling an institution to embrace all children.

In any truly inclusive educational setting, all students must feel accepted as ‘one of the family’. As Savage7 points out, an early years facility can hardly claim to promote equal access if ‘a group of boys dominate the outdoor play area … or a child with impaired sight tends to be marginalised at story time.’

The Implications of Disability

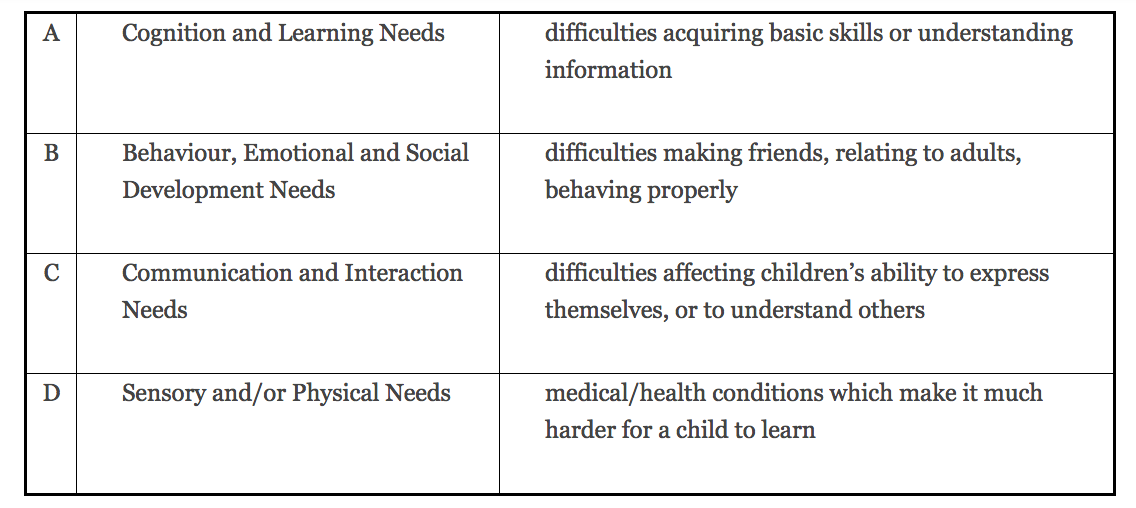

The UK’s SEN Code of Practice8 arranges SEN needs as outlined in the following table:

All experienced academics and practitioners highlight the critical importance of early intervention. However, as Roffey9 cautions, childcare professionals must be aware families may not always offer their full support:

‘Their reluctance may stem from having experienced a lack of sensitivity and from feeling blamed or guilty as well as having to struggle to accept their child’s difficulties.’

Such attitudes are not hard to understand if one considers the multiple extra burdens families are asked to cope with:

– care for a child with SEN can be exhausting, impacting on the lives of parents and other siblings;

– bringing up a child with a disability is always more costly;

– negative community attitudes lead to social exclusion, and disability still carries a stigma in some cultures;

– a child with SEN needs is more likely to experience poverty, and poverty exacerbates impairment;

– a child’s longer-term future can be a particular worry for families.

You can learn more about SEN friendly settings here.

For childcare professionals with responsibility for children with SEN, a sensitive attitude is a must. Whilst (as regards disability) our wider society is often embarrassingly wedded to stereotypes and sensation – think of the silver screen portrayal of Dickens’ Tiny Tim, and news coverage of the trial of Oscar Pistorius – most children with a disability yearn to be accepted on par with their friends, and don’t wish to be defined by their impairment.

Is Your Setting SEN Ready? – Free Email Course

Beyond sensitivity, professionals must ensure they are aware of the basic implications of any condition or disability, otherwise, as Capel et al.10 note, they risk unforgivable errors:

‘… children who have obvious physical disabilities such as cerebral palsy often find they are treated as though their mental abilities match their physical abilities when this is not the case.’

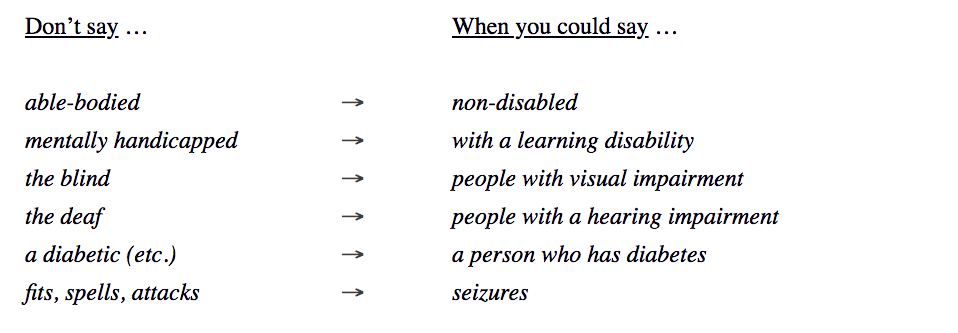

Special Educational Needs and The Language of Inclusion

Nowhere is acceptance more clearly offered, or withheld, than via the language society uses to communicate with, or about, those with disabilities. In an early years setting, professionals should use respectful language which acknowledges that children with SEN, just like their classmates, are active individuals who have the same right to grow and take control of their own lives.

For example:

- Wheelchair users don’t think of being ‘confined to’ a wheelchair – it’s a mobility aid.

- Avoid negative medical labelling: ‘suffers from’ implies a patient in constant pain and despair. Use ‘has epilepsy’ (etc. as appropriate) instead.

And finally…

The best way to gain the confidence of a child with SEN is to use a normal tone of voice while speaking directly to the child – even if they have an interpreter. Also, never finish the child’s sentences – just give them plenty of time to respond. For those unfamiliar with SEN environments, there can seem lots to remember, but with a little background work it’s more about attitude than anything else.

Playworker Adrian Voce gives a actionable breakdown of SEN language in his article: Special, disabled or unique? Language is important, but attitude is everything.

So don’t worry endlessly about political correctness; if you can relax and speak to a child with SEN using the everyday language you would use with any other child, you’ll find the visually impaired will be very happy to ‘see’ you, and wheelchair users will be simply queuing up to ‘go for a walk’ with you!

[References]

You must be logged in to post a comment Login