Child Development

Why It’s Vital That We Teach Children to Sing

Crying out is how we all announce our arrival into the world, and this for humans forever remains an instinctive form of expression:

‘We are meant to use our vocal chords not merely as a valve to prevent unwanted bits getting into our air passages, but to communicate with others. Language has evolved to carry out this function, but the primary means of vocal expression is the cry, and from that develops the singing voice.’ (Jones, 1999)

A child’s earliest experiences of communication occur within the context of mother-child bonding. Having already learned to recognise its mother’s voice while still in the womb, a newborn child is then greeted by the delightful lilting, cooing tones of ‘motherese’ – the ultra-expressive tonal language a mother naturally uses when talking to her precious infant. Research has demonstrated that babies prefer this exaggerated form of speech, which is marked by the use of a broader range of pitches as well as joyous swooping and gliding effects. These features make it much easier for a baby to differentiate such communications from the general swirl of adult conversational tones, which in contrast are much more restricted in range and far less expressive in style.

Passive music

It was once the case that infants would fall asleep to the sound of a mother’s lullaby, and many would also hear their father’s repertoire of work songs as he toiled throughout the day. But now those days are gone by, many children never hear such songs, nor do they experience family-time singing songs together, hearing instruments played, hymn singing during church services, and many other spontaneous opportunities to enjoy active music making. Whilst it’s true babies and young children will encounter many devices which play lullabies and children’s songs, the absence of any element of human performance – no sense of the sight, sound and feeling of someone singing in the room – means the stage is already set for the child to settle for becoming a passive consumer of musical experiences.

Today’s growing child lives in a world where music’s ability to entertain, divert and thrill the senses, often creating sounds which live long in the memory, has been almost completely detached from any social or personal music making. The music and entertainment industries now offer us flawless musical performances which are electronically enhanced in an effort to capture and hold our attention in an environment crammed with all kinds of music media. As a result, most of us are denied the pleasure and health-giving benefits of vocal participation, and our young fledgeling singers never get to use their vocal chords for much more than speaking, and soon learn to become part of what some have called our silent culture.

Language and communication

Developing as a passive receiver will inevitably limit a child’s ability to learn and progress – the Bercow Report, for instance, has commented that language and communication:

‘… is a skill which has to be taught, honed and nurtured. Yet… children’s ability to communicate, to speak and understand [is] taken for granted.’ (Bercow Report, 2008)

The relentless decline of singing as an everyday feature of our culture has thus robbed preschool children of regular and active access to a store of nursery rhymes and songs which once proved a valuable means of acquiring and developing such language and communication skills. Of course, a childcare setting is ideally placed to restore at least some balance – if there are adults prepared to communicate through song and set up an environment which simply encourages children to sing.

Many otherwise-confident childcare professionals may be daunted by the prospect of helping children to sing, which is just more proof of where our culture is going. However, the potential benefits for children are immense, and any adult who starts to sing will gain a range of health, mood and confidence-boosting benefits too. Remember too that:

- you don’t have to be a ‘trained’ singer – in fact, hearing the resonant tone and more-aggressive attack of an accomplished singer is often quite intimidating for young children,

- young children are not music critics – if you are calm and confident, they will follow your lead (as they do in all the other activities you invariably model as a ‘non-expert’),

- the vital component is giving children the opportunity to sing, which helps to develop their speech patterns and teaches them how our language is constructed.

It’s also helpful to remember that the children’s songs you use are designed to teach a whole host of things – alphabet, counting, stories, culture, the natural world, and a million other topics. Therefore it’s best to just sing and enjoy the majority of songs for what they are, leaving yourself just small, manageable repertoire of songs where you are actively seeking to help children ‘find their voices’.

Finding a child’s singing voice

Research suggests that young children learning to sing will find it easier to learn songs if the process is approached in a certain order:

‘… children first struggle to get hold of the words. Next the child appears to capture the rhythmic detail of the song and only finally to concentrate on the melodic detail.’ (Glover, 1998)

Although the children are unlikely to notice any difference in your presentation, learning a simple song should thus focus first of all on learning to sing (or even speak) the words of the text. You should then look to clarify any rhythmic problems your children experience, and only then move on to pitch. With some familiar songs, this process may take no more than a few minutes, though with more difficult material it may need repeat sessions to gain enough confidence with the text to pass on to the rhythm. Initially, you can settle for a ‘working grasp’ of each phase, gradually refining the performance of any song over a period of time.

The character and learning aims of the songs you use should be the principal factors governing your approach. So choose very simple songs with no complex actions if you want to focus on pitch, and tunes which easily lend themselves to actions or movement if you want to emphasise rhythm and pulse.

Singing a melody

During free play young children will naturally use a full range of vocal expression, but moving straight into tuneful singing will only reveal the fact that they cannot yet control the process of adjusting pitch. Therefore initial approaches should aim to reinforce the idea of vocal flexibility. Use this as an opportunity for fun by speaking in odd voices, or cartoon characters etc. and getting the children to copy – you might, for instance, want to adapt a favourite story for this purpose. Ask your children to make animal noises too – perhaps a long drawn out moo, baa, meow, a mousey squeak, or a lion’s roar.

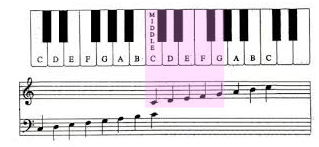

Though not all published children’s songs reflect this limitation, young voices have a very narrow range indeed. As can be seen in Figure 1 below, this extends from middle C on the piano to the note G above.

Figure 1 A young child’s approximate vocal range from Middle C up to G

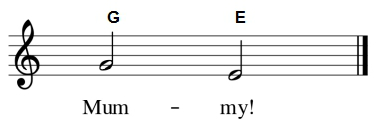

The child’s speaking voice will be pitched somewhere here, and the first task is to free up that speaking voice enough to begin up and down pitching. After first modelling how a child normally speaks to friends, you can then demonstrate what happens when they want to ‘call Mummy’ when she is far away at the bottom of the garden. This type of call will be: much louder than a speaking voice, at the top of the child’s vocal range, and will probably use a different pitch note (G down to E) for each of the two syllables in the word ‘Mum-my’ – see Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 A two-syllable call using a falling pitch sequence

This routine will help children to gradually become accustomed to the idea of high and low pitches. You could also add this concept to their animal sounds. For instance, how would a lamb call out to its Mummy?

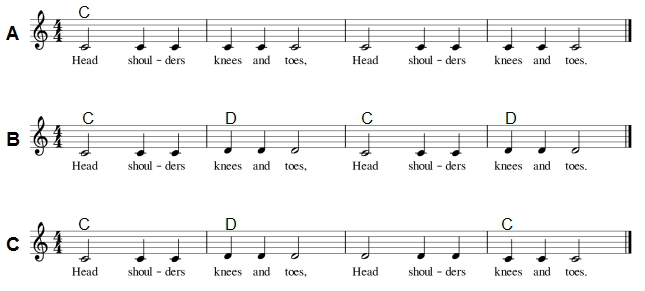

Next comes chanting together, first on one note, then on two. Figure 3 below uses the rhyme ‘Head, shoulders, knees and toes’ and shows how to create three versions, each with a slightly different arrangement of pitches, but any simple set of words will do.

Once the children are starting to grasp the notion of moving up and down in pitch, you will then be ready to start looking at some simple tunes to hone the pitching skills of your developing singers even further. At this point, you will already have a blueprint for tackling songs – words, rhythm, melody – and will then need to acquire some song materials suitable for younger children.

Song resources

It’s essential to choose music which has been carefully arranged to accommodate developing singers. The Voices Foundation’s three-part series ‘Inside Music’ has an excellent first book for Early Years: Age 0 – 5 (view at http://www.voices.org.uk/shop). This is a new edition by Katie Neilson (including a CD and MP3 for all songs) which can be used as a stand-alone resource.

There are, of course, many other song collections available for young singers at the Foundation Stage – the publishers A & C Black, for instance, have a long-standing reputation for producing quality music resources for this age range.

More Foundation Stage resources available here (https://www.starland.co.uk/publications-26-resources.html)

Accompaniment and performance

Most simple songs sound well with voices alone, or perhaps supported by a gently strummed guitar or a quiet keyboard. Whilst the use of a CD backing track may give adults with little experience some extra confidence, excessive classroom use can lend a karaoke flavour to music sessions which, for all its attractions, will do little to develop singing abilities. Those who feel they need some support should perhaps partner with other more-accomplished adults, and/or resolve from the outset to work without backing tracks as little as possible.

Live music making has its attractions for adults too. So parents who wish to help/join in with the singing should be welcomed, just as long as their participation reinforces the social element of such activities without compromising the learning opportunities. For instance, it may become a treat for all to augment your musical forces in this way for special celebrations.

John Cleary is a musician and former Head of Music who has also worked as a peripatetic instrumental teacher.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login