Child Development & Technology

The Role of Digital Play in the Early Years

Today’s pre-school children were born into the digital age, so for them it is already simply a feature of their everyday lives. But for parents and childcare professionals, who have experienced a pre-digital age, acceptance will always be more nuanced. After all, the arrival of digital devices has primarily given them choice. They can now choose to embrace digital play options, which come with a need to learn new skills, yet equally, they can often decide to stick with non-digital options. But more than this, past experience gives adults perspective and in many cases allows them to make value judgements about the advantages and disadvantages of digital devices young children can now access.

Digital Play: Adult Approval and Disapproval

Young children are drawn to digital devices for a whole variety of reasons, not the least of which is that they afford a host of playful experiences. But where parents and educators have concerns or reservations about digital play, these are usually focused on three primary areas of concern:

- Health and well-being

- Brain development and cognition

- Development of social and cultural competence.

Focussing on just one area of concern (video games) Whitebread (2012) commented:

‘While it is clearly the case that we live in a digital society and accordingly video games and other screen-based technologies are a part of 21st century children’s lives, the evidence that this is at the expense of, or directly opposed to, physical and outdoor play is not clear … if the amount of time children spend playing outdoors has declined, this appears to be a result of changing attitudes to risk in urban environments rather than to an increase in video game technology … there is some evidence that well-designed video games can enrich play resources for children and their families.’ (Whitebread et al., 2012)

Nevertheless, most parents see digital technologies as having largely positive benefits: they are a valid form of children’s entertainment, offer constructive play options which stimulate imagination and promote social development, and can support early learning. However, it can often be difficult to quantify what goes on during digital play, and just as tricky to see how looking at screens etc. fits with established theories of children’s play.

Theories of Play

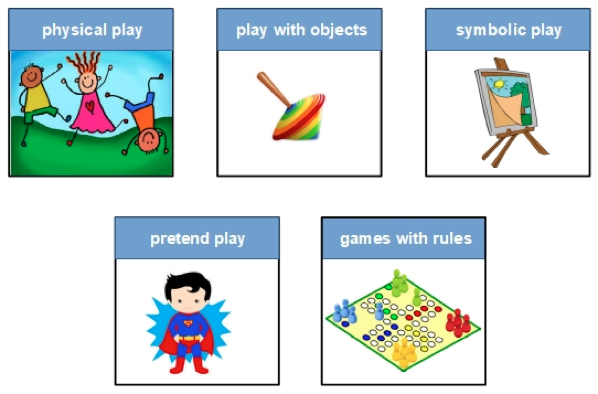

According to Whitebread (2012) and as outlined in Figure 1 below, contemporary psychological literature divides play into five broad types:

‘These are commonly referred to as physical play, play with objects, symbolic play, pretence/ socio-dramatic play and games with rules. Although each type of play has a main developmental function or focus, arguably all of them support aspects of physical, intellectual and social-emotional growth.’ (Whitebread et al., 2012)

Even though there is a degree of overlap in some activities, these five easily recognisable categories are a practical way of thinking about the play of pre-school children: physical play is energetic and sporty; object play can use toys or just everyday items; symbolic play can be drawing, reading or other media; pretend play involves play-fantasy worlds; and games with rules satisfy a child’s need to understand and control their world.

Meanwhile, earlier theorists such as Bruner, Vygotsky and Dewey emphasised the sociological functions of play as a natural form of learning. Vygotsky, for instance, considered that play was the primary means by which learning and development took place. According to Vygotsky (1976), all early play was a precursor for what he described as ‘mature play’. To illustrate this concept he took the idea of a child playing horses and thus ‘riding’ a stick. For Vygotsky, it was a mature imagination which allowed the child to play happily with the stick as a symbolic representation of a real horse. Such maturity of thought showed the child could understand symbolism: the idea that one thing could stand for another, a vital concept which is the gateway to all of the more advanced forms of learning.

Play Interactions

Piaget emphasised the important role of play in a child’s development, but largely considered teachers and other adults as guides and peripheral facilitators. However, Vygotsky, Bruner and others believed that the essentially social nature of learning and development meant that adults often tended to interact with children and adopt a carefully nuanced supportive role. Often termed ‘scaffolding’ or ‘bridging’, such subtle interventions capitalised upon play situations in order to help children make meaningful connections to enhance and extend their understanding.

According to Vygotsky (1978), play was the time when children were potentially most likely to be operating at a level beyond their development, which is one reason early years policy now promotes the importance of such adult-child play interactions. However, Plowman & Stephen noted that while most early years professionals employed scaffolding techniques across a number of curriculum areas, this was rarely the case with computers, even when the children were clearly ‘complete novices’.

‘There were few examples of peer support; adults rarely intervened or offered guidance and the most common form of intervention was reactive supervision.’ (Plowman & Stephen, 2005)

Facilitating Digital Play

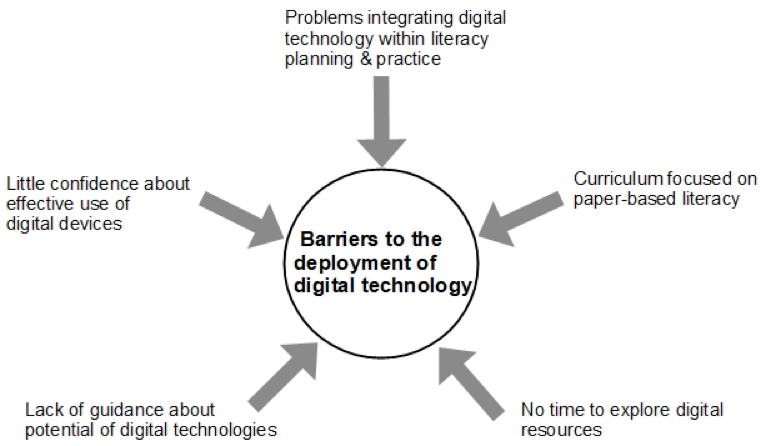

As Figure 2 below highlights, a number of constraints in childcare settings have made it genuinely difficult to integrate and support digital play in the early years curriculum.

Despite such limitations, the Royal Society’s ‘Shut down or restart?’ document (2012) makes it quite clear that continuing to ignore digital literacy in such ways is not an option:

‘Digital literacy does need to be taught: young people have usually acquired some knowledge of computer systems, but their knowledge is patchy. The idea that teaching this is unnecessary because of the sheer ubiquity of technology that surrounds young people as they are growing up – the ‘digital native’ – should be treated with great caution.’ (Royal Society, 2012)

But even though play is an ideal opportunity to introduce digital technology, moving forward will take more than statements that teaching digital literacy is necessary. Stephen & Edwards, for instance, note one significant issue concerning some theories of play often applied to digital play contexts which have remained unchallenged and unadapted for decades:

‘there is … no reason for ideas about play to remain static and historically embedded in the time from which they came. Like knowledge in other areas, knowledge about play is capable of evolution, meaning that new ideas about digital play are becoming increasingly possible.’ (Stephen & Edwards, 2018)

Digital Play

As Marsh & Bishop (2014) and many others have noted, popular culture references have long been a significant strand within younger children’s play. And since the early 20th century, it has mostly been the dominant technology of the era – radio, silent films, ‘talkies’, TV, and now digital devices – which has been the primary source of this cultural material.

All of these media have had a powerful influence, for example on children’s pretend play. However, the advent of computer technology has arguably introduced a new dimension. Now it is possible for children to play in virtual worlds which can be astoundingly detailed and realistic. As Stephen & Edwards observe:

‘… play is no longer experienced as a strictly real or virtual activity. Rather, research points to an increasing blurring of the boundaries between the digital and the non-digital.’ (Stephen & Edwards, 2018)

Marsh (2010), Plowman, McPake & Stephen (2010) have all reported that today’s children make little or no distinction between digital and non-digital worlds. As a result, these authors question whether it is now particularly helpful to maintain a distinction between play in real and virtual environments. Indeed it has been suggested that the concept of a continuum linking real play at one extreme and digital play at the other would be a more accurate reflection of many play experiences in the 21st century.

Play as a Continuum – An Example

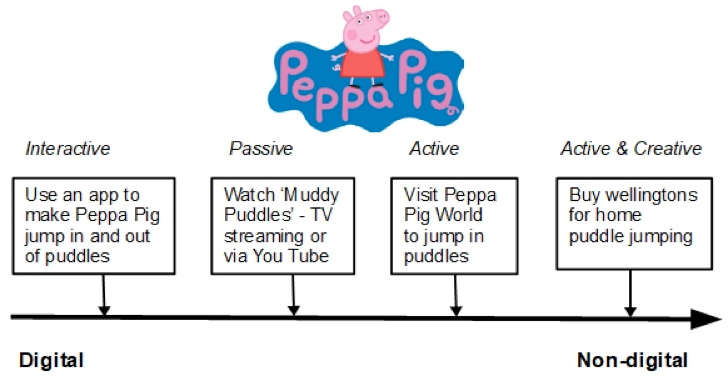

Developing Marsh’s (2010) concept of a play continuum, Edwards (2014) has shown how play focused on Peppa Pig, a popular media character aimed at young children, might be adapted to suit a range of circumstances. (See Figure 3)

In this example, a young child might play with friends using an iPad or computer, exploring an app adventure in which they could control Peppa’s digital-world actions such as jumping into puddles. This is clearly an interactive activity in which the child participants can choose a range of actions within a digital adventure play environment.

In a directly related follow-up, the children could watch the real ‘Muddy Puddles’ episode of Peppa Pig, either via YouTube or as content streamed to a Smart TV. Whilst this may seem a relatively passive option, it would nevertheless give children plenty of mutual enjoyment in a shared social context and certainly offer plenty of ideas to try out during future group or individual free play around the general theme.

A family visit to a themed attraction such as Peppa Pig World would surely include a vibrant mix of digital and non-digital experiences. And doubtless there would be opportunities to practise and enjoy the puddle-jumping (in a realistic, digital-style environment) which so captivated their favourite character.

Sign Up to Receive this 20-Part Activity Email Series

Finally, our ardent puddle jumpers would now be busy persuading or imploring their parents to go out and buy the ‘tools for the job’. This might involve a trip to the shops to find a perfect pair of wellingtons to match those sported by the digital star – who at this juncture could not seem more ‘real’. This would transform future walks in the rain for a happy, if somewhat damp and muddy, child! A thoroughly non-digital experience driven by enduring memories of a digital-world character.

This seamless series of events would simply be enjoyed by any child motivated to participate. There would be no digital/ non-digital boundaries, no limitations to overcome, and no transitions to manage in order to unlock the substantial gains and benefits.

Mapping Digital Play

To explore the modes and content of modern children’s play, Edwards (2013) began to research and map what happens during typical play. The study results gathered from parent and child interviews were illuminating:

‘… traditional play was still present in the family home. This included outdoor play, construction play, fine motor play and pretend play. However, this traditional play almost always integrated with a form of digital participation by children.’ (Edwards, 2013)

In the types of play mentioned:

- outdoor play might include shifting sand with imaginary Bob the Builder diggers,

- construction play might involve building with Harry Potter themed building blocks,

- fine motor play might entail screen drawing with an iPad app, and

- pretend play might call upon an extensive cast of digital adventure charcters.

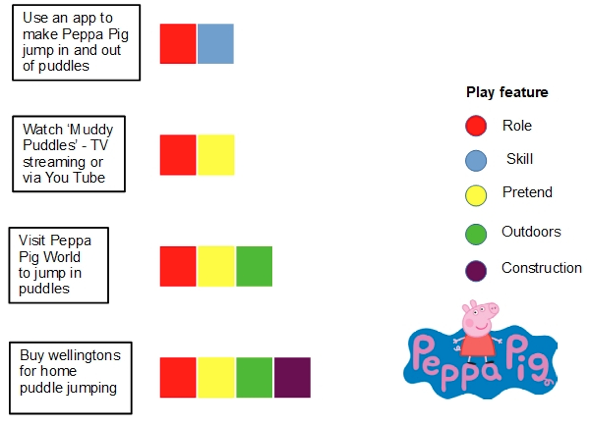

Revisiting the Peppa Pig activities (see Figure 4 below) will demonstrate what mapping can reveal about the content of play episodes.

* Though this example outlines the methodology involved, practitioners will find the authentic Susan Edwards at-a-glance web-mapping tool offers a far superior and more comprehensive method of achieving the aims discussed below.

The diagram offers a way of identifying which major kinds of play and/or learning attributes were notionally present in each play phase. Not only does this kind of analysis show the play features involved, it also allows parents and practitioners to see the extent of digital and non-digital content within each activity.

So for childcare professionals this kind of mapping could be used both to analyse and plan a range of play events to ensure an integrated and balanced blend of digital/ non-digital play content. Furthermore, such a tool could form a key part of any initiative designed to demonstrate how an early years setting was actually covering the requirement to teach digital literacy and thus properly prepare their children for life as 21st-century citizens.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login