Child Development & Technology

How Does Technology Affect Children’s Creativity?

Digital technologies of numerous kinds make modern lifestyles more comfortable for us all. But for young children born into the digital age such devices are merely a feature of their native environment. And as so many technologies start to converge, so the flexibility of their application continues to grow. A contemporary smartphone is a good example: This device was originally designed to facilitate mobile telecommunication but now comes (as standard) equipped with a powerful camera, the ability to capture video footage, act as a satnav, and a whole lot more.

So those children presently attending early years settings will grow up in a world where their prospects will often be determined by their ability to function creatively by effectively deploying these digital resources. But first of all, what do we mean by creativity? And can young children really be expected to innovate?

What is Creativity?

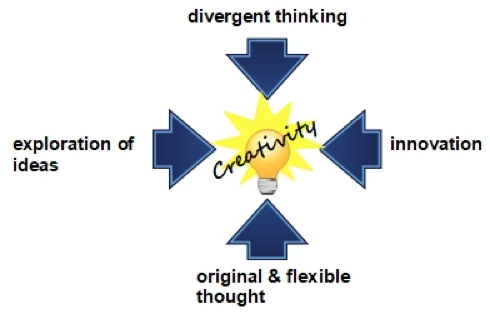

Different fields and disciplines all seem to have their own unique definition of creativity. So even though we recognise a creative idea it can sometimes be more difficult to explain why it should be considered creative. Although individual experts may well choose to highlight a number of different aspects, Barnaby & Burghart (2017) identify four important characteristics of creativity which are generally considered essential: divergent thinking, innovation, original and flexible thought, and exploration of ideas (see Figure 1 below).

Creativity theorist Robert Sternberg (2003), for example, believes that children’s creative thinking must be imaginative, novel and produce outcomes which have value. But whilst it is easy to demonstrate children are imaginative, many would not accept that early years children are capable of producing original ideas, nor would they necessarily agree these youngsters could generate ideas of particular value. However, considering this from the perspective of the individual, Sternberg argues that (for a child to be creative) it is only necessary to show the notion is new for that individual – which is why he tends to use the term ‘novelty’ rather than originality. And likewise, an idea need only be shown to have value for the individual to satisfy that criteria also.

Educationalists may once have considered the arts to be the natural home of creativity, and it remains true that pursuits such as painting and drawing, craftwork, dance, drama and music all demand and promote creative thinking. Nevertheless, it is now accepted the modern world defines creativity much more broadly, which clearly has implications for creativity within the curriculum. In the field of science, for example, creativity drives effective problem-solving as possible theories and solutions are voiced long before trial-and-error testing and verification begins.

Young Children in a Digital World

Practitioners must be mindful of how today’s children interact with digital technology: It is a phenomenon which exists everywhere in their lives. For instance, in the home environment, a young child will observe how parents and perhaps older siblings interact with devices. Not only will children wish to learn by imitation, but such technologies have also become important cultural tools, which means they are becoming part of the fabric of children’s lives. That, in turn, means parents, and the wider family will naturally wish even the youngest children to be able to benefit from these resources. So, as research by Plowman et al (2008) discovered:

‘… rather than children simply ‘picking up’ technological skills in the family home, these skills were in fact co-built and supported … through the use of processes such as direct instruction, modelling, experimentation, observation and play with technological artefacts.’ (Plowman et al, 2008)

However, with some technologies (e.g. screen-based media) it may be wise for parents to ensure young children’s usage remains appropriate for their age and stage of development. Above all, there needs to be a good balance of active, social and creative elements to avoid any risk of slipping into an unhealthy, sedentary lifestyle.

In essence, this is much the same as introducing a child to books and magazines, which equally should be properly matched to the needs of the individual. So with digital devices, as with books etc., the key is to use unobtrusive support and supervision, both to instil proper habits and to make sure that screen time, for example, stays within acceptable norms.

Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) and Digital Creativity

The EYFS (2018) specifies Expressive Arts and Design as one of its seven areas of learning. This area-specific guidance is cast in broad terms and promotes digital creativity which provides:

‘… opportunities and encouragement for sharing … thoughts, ideas and feelings through a variety of activities in art, music, movement, dance, role-play, and design and technology.’ (EYFS, 2018)

The related early learning goals for Expressive Arts and Design in the same document suggest children should be encouraged to: explore by singing songs, making music and dance – ‘and experiment with ways of changing them.’ And in doing so, they should ‘use and explore a variety of materials, tools and techniques, experimenting with colour, design, texture, form and function.’

Elsewhere in another area of learning, Understanding the World, the EYFS framework expects children to have ‘opportunities to explore, observe and find out about people, places, technology and the environment.’ Here, it is important every child should ‘recognise that a range of technology is used in places such as homes and schools.’ And in addition, they should be taught to ‘select and use technology for particular purposes.’ (EYFS, 2018)

The Creative Learning Environment

Whilst it is broadly accepted that digital technology offers a powerful and flexible means of enhancing creative learning, as with any other educational resource it can only perform this task when skilfully used to drive and support best early years practice. Once again, Barnaby & Burghart (2017) define the priorities for digital creativity:

‘Children require an enabling environment and positive relations between themselves, their family, practitioners and other children, in order to develop their abilities, confidence and independence.’ (Barnaby & Burghart, 2017)

When it comes to nurturing creative thinking while reinforcing children’s cognitive development and improving their social and emotional well-being, practitioners can be guided by the work of experts such as Piaget, Bruner and Vygotsky who have explained the thought processes and phases which characterise the developmental journeys our children undergo.

Early learning pioneers such as Froebel and Montessori highlighted the importance of freedom of choice, whilst Dewey considered children learn best first-hand by actively doing things. Piaget’s vast contribution to the field suggests pre-school children are in what he termed a ‘pre-operational’ phase, gradually developing symbolic, make-believe play as their language skills improve. At this time, Barnaby & Burghart believe:

‘… toddlers should … be able to use replica technology and digital toys in self-directed, self-created, role-play activities. They can also be guided in the use of simple screen-based media, permitting symbolic play through the use of drawing packages and programmable toys.’ (Barnaby & Burghart, 2017)

Practitioner guidance and subtle interaction, of course, implies familiarity with the concept of scaffolding as exemplified in the work of Vygotsky and Bruner. And if an early years setting is to allow children to access a range of developmentally appropriate digital and non-digital resources, and make links between these formats to develop their creative thinking in different contexts, then childcare professionals will have to plan their resources carefully. One effective way of setting up resources is to use Tina Bruce’s (2011) concept of ‘free-flowing play’. This method advises giving children both the time and the space necessary to explore a range of freely chosen, child-led activities designed to offer creative opportunities which have the potential to fire their imagination.

Sign Up to Receive this 20-Part Activity Email Series

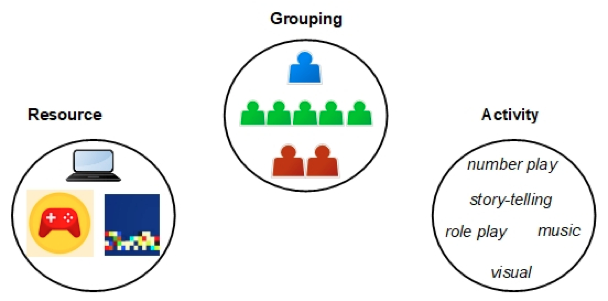

Furthermore, as Figure 2 illustrates, this planning will need to go beyond, for example, simply keeping screen-based digital media separate from sand and water play. Play resources will also need to be flexible enough to allow for children at different stages of development, as well as those who may have their own individual needs, to take advantage of creative learning opportunities. Here in particular, well-differentiated resources can enable those of mixed abilities to participate fully in every curriculum activity.

The above diagram gives some examples of three possible approaches to differentiation (which can also be used in combination):

- by resource – where different software, games and other elements could suit a range of abilities,

- by grouping – where participant numbers could be flexibly adjusted to better satisfy different social needs etc.,

- by activity – where a mix of topics could be used to accommodate different preferences.

Creative Digital Resources

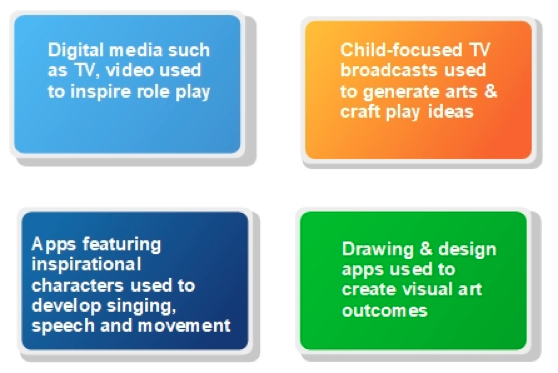

Within the digital domain there are a range of screen-based options which can be used as creative tools. Figure 3 below suggests some of the many ways they can enable children to enjoy experiences beyond the classroom, engaging in real or imaginary worlds where they can experiment, creatively explore, and become immersed in magical environments. Apart from the inherent value of the on-board experience they offer, these resources can also act as a catalyst for further creative ideas – which may emerge much later when the child is engaged in some non-related activity.

Mixed-Mode Activities

The advent of powerful hand-held digital devices such as tablets and smartphones, and/or recorders for capturing audio and visual content has facilitated the blending of ‘real’ and virtual learning environments. This potentially allows for the development of projects which approach a learning topic in a variety of ways, as well as offering the possibility of creating a digital multimedia record of outcomes for later discussion and display on a classroom electronic whiteboard.

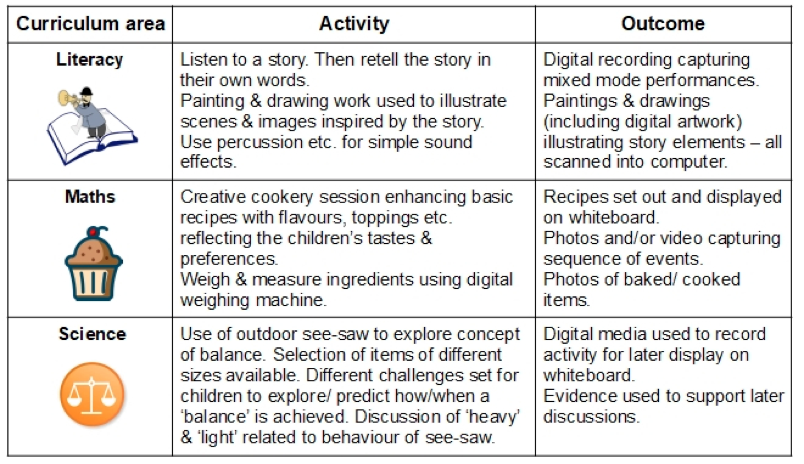

Three examples from different curriculum areas are shown in Figure 4 below, and include some possible ways of presenting a topic, while also noting some of the anticipated outcomes.

Each activity offers inherently creative tasks, but the inclusion of digital resources adds a new dimension which must surely come closer to the kind of real-life educational and working experience today’s pre-school child is destined to enjoy.

To take just one multimodal learning activity described by Yelland & Gilbert (2017) – creative and artistic play – in a little more detail: Using a tablet computer to create electronic art would give children the opportunity to experiment with different artwork media and save the outcomes for later display. With a good arts package, the user could not only use a pen as an input drawing device but also switch to using a finger as a direct-input device. Such apps will usually have a broad range of input tools and features (e.g. stamps, magic paintbrushes), allowing children to produce more sophisticated pictures than they could manage through traditional painting and drawing alone. The range of different options available would also give children plenty of opportunities to discuss their evolving work and the creative choices they made with supporting adults.

An extension of this activity could be arranged as a self-portrait drawing session: Looking at their face in a mirror, each child could draw themselves as an electronic image, then create a further self-portrait using pencil and paper. Each image could subsequently be captured and displayed on a whiteboard. This activity would generate many kinds of interesting talk during the various stages as well as at the presentation of final outcomes.

In any creative task, (traditional, digital or mixed-mode) the essential requirement is to choose whatever is the most appropriate medium and method to best develop creative learning. Today’s digital world has increased the range of creative options available, but it is always important to incorporate these elements as seamlessly as possible, so they are never allowed to become the sole focus of any project.

And finally, Barnaby & Burghart remind us:

‘As young children are growing up in a world in which they are exposed to and engaged with a wide range of digital technologies, it is important to be mindful that their natural ability and propensity to create is being promoted and not suppressed by this medium.’ (Barnaby & Burghart, 2017)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login