Childcare Environments

Virtual Reality: Harnessing the Power of Illusion

Wise parents understand that young children have always spent lots of time in their own virtual worlds where, thanks to the power of magic and fantasy, they alone are in complete control and absolutely anything a child can imagine becomes instantly possible. However, the digital age can now bring us virtual worlds in which playful make-believe can be enhanced to such an extent that it is experienced as ‘reality’. Given the powerful appeal of such technology – as demonstrated by the recent Pokémon episode – this article outlines some of its core concepts and potential applications. In addition, some issues are raised for debate and discussion, which parents and practitioners may perhaps find themselves having to address far sooner than they might wish

.Simulation basics

Virtual Reality (VR) is a totally immersive technology. Once you’ve put on a VR headset, you can explore a 3D landscape simply by turning your head. The new world you encounter may be computer-generated graphics, pre-recorded video, live footage streamed from some remote destination, or even a blend of these options. Accumulating evidence shows the mind rapidly accepts the illusion of presence, and Chatfield (2016) reports that: ‘Above all else, it’s a startlingly emotional experience.’

A related technology with a complementary range of applications, Augmented Reality (AR) takes a different tack and superimposes relevant images and/or other digital data onto a user’s visual experience of their existing environment. This creates a machine-enhanced composite view perhaps involving audio, video, graphics or GPS data, which offers the user significant in-situ advantages.

Observant readers will (correctly) conclude that this means the ‘live’ appearance of Pokémon figures was achieved using time and GPS data, and thus is a clever application of AR technology. However, what may be less well-known is that author L. Frank Baum, who also wrote ‘ The Wonderful Wizard of Oz’, was the first to offer a literary account of what we now know as AR in his 1901 novel entitled ‘The Master Key: An Electrical Fairy Tale, Founded Upon the Mysteries of Electricity and the Optimism of Its Devotees’. Here, as Parkin explains:

‘… [a boy hero] is given the magical spectacles by a demon. [Following the hero’s gaze, his eyeware displays a host of data about anything he look at.] After a fortnight’s adventuring, he concludes that neither he nor the world is ready for the specs. On the third week, he returns the invention until, he says, that time when humankind knows how to use them.’ (Parkin, 2016)

Virtual reality: a technology come of age?

The current investment the likes of Apple, Sony, Google, Facebook, Microsoft and LG are making in both VR and AR technologies suggests that time really has now arrived. And beyond obvious military applications, simulation apps and systems are becoming common in sport, entertainment & leisure, and healthcare, plus a host of marketing and industrial applications.

Whilst many of the headsets, custom eyeware and hi-tech clothing required to access VR and AR are often quite expensive, Google Cardboard offers a DIY (cardboard and plastic) ‘headset + your own smartphone’ VR experience for pocket money prices. This allows access to well over 1,000 VR apps (many free) covering action topics such as a Jurassic world, a helicopter ride, deep-sea diving etc., all of which convincingly illustrate the thrill/excitement aspects of fully immersive VR. Meanwhile other apps, such as ‘Bloodstream VR’, which locates the viewer inside the body’s pulsating ‘virtual circulatory system’, have a rather more direct educational focus.

Corporate education

Historically, the development of technology has always been mirrored by a parallel growth of media content supporting mainstream education, especially as regards the creation of ground-breaking material for the early years sector. UK pioneers such as the BBC have now been joined in this endeavour by global corporations like Apple and Google. One result of the combined influence of new multinational interests plus an endless stream of new technology initiatives has been the emergence of in-house play and educational materials which make less and less attempt to reference the UK’s own educational system. Though educators may find this situation anything from quirky to thoroughly unhelpful, commercial institutions in their turn would be quick to complain about how slow education has been to tap into the benefits of their investment – and Kaye’s comment would seem to imply they make a good point:

‘While there are a number of books with ideas for using technology with early years … there are fewer which address the pedagogy relating to their use.’ (Kaye, 2016)

Consumer initiatives

Evidence for just how keen major players are to advance the development of VR as an educational tool is not hard to come by: According to Heathman (2016), Google’s Expeditions team is currently arranging to bring a free VR experience to one million of the UK’s school children. Meanwhile, Ramli (2016) reports that the Chinese are developing e-learning software using ‘cost-effective platforms to develop the content’ which exploits Western VR technologies to help educate China’s vast numbers of school-age children.

Considering the consumer market more generally: Google sold five million of its Cardboard headsets worldwide in the two years following its introduction in 2014, while Nintendo’s Pokémon achieved viral exposure on a global scale during the summer of 2016. This would seem to suggest that AR and VR technologies will steadily continue to penetrate the home entertainment market, allowing new generations of young children to become familiar with this mode of experience. That in itself will allow companies to further develop the educational potential of simulation technologies, and also enable these interests to tighten their grip on the field.

Digital play and virtual worlds

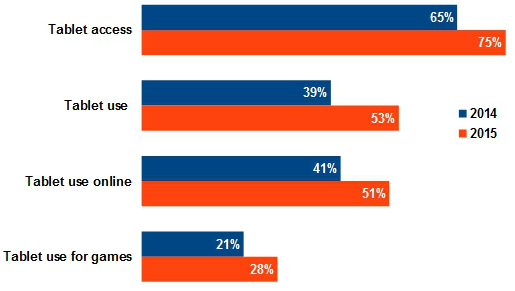

The fact that most of today’s children have increasingly limited opportunities for outdoor play is another feature likely to promote the use of digital devices for indoor play. Ofcom’s UK research into the media habits of 3-4 year olds shows that, alongside the use of gaming consoles, tablet computers are becoming the favoured option for digital play. Figure 3.1 features an extract from the Ofcom data for 2015 which shows that more than 7 out of 10 children aged 3-4 years now have tablet access at home.

Figure3.1 Growth of home tablet use by children aged 3-4, across 2014 and 2015 (Ofcom, 2016)

Whilst we all accept that early childhood is a special time when a child’s imagination is free to roam well beyond strictly practical, everyday realities, many express some concern about the impact of prolonged exposure to digital virtual worlds during play. Though this is an area where detailed longtitudinal research is still needed, Marsh’s own research with young children concludes:

‘For the children in this study, it was clear that the relationship between online and offline play was close and that there were many similarities between them. Primarily, play was a social practice that was constructed through interactions with others; this is the case both in the virtual world and the physical world. Many categories of play remain the same across these spaces.’ (Marsh, 2010)

SEN initiatives

VR already plays a role in helping children with special needs. Haddad, for instance, reports that for those with learning disabilities:

‘Virtual reality provides a simulated environment which allows a child to practice or enhance various skills which can be transferred to the real world. Through the use of avatars (graphical representations of human beings), a user can socialize with other people and participate in activities, such as cooking, using a computer, going shopping … – all without the risk of injury or fear of public embarrassment.’ ( Haddad, 2015)

And VR has also been used to help those with autistic spectrum disorders (ASD) both for general social cognition (Didehbani et al., 2016) as well as for targeted practical functions such as crossing roads safely (Josman et al., 2008). The advantage for participants once again being that a virtual world is a much more forgiving place to learn about interacting with others.

The development of empathy

Reverse simulation is a unique feature of VR which is proving to be one of its greatest assets. As part of their 2016 ‘Too Much Information’ campaign, the National Autistic Society have released a 360-degree VR video which depicts an everyday episode in a busy shopping centre as seen through the eyes of a young boy with ASD. Through this VR experience, viewers can gain some appreciation of the terrifying experience this represents for those afflicted with autistic conditions.

A powerful training tool

Whilst we are all called upon to show empathy from time to time, it is an absolutely vital component for those in education and caring professions which depend on optimum social interactions. Thus it may be helpful to close by examining Chatfield’s account (quoted below) which outlines the vast and inherently powerful range of training and therapeutic opportunities which VR can make available – giving practitioners vivid insights which might otherwise take years to acquire:

‘… a study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry Open [Falconer et al., 2016]… devised a test where participants entered a virtual environment by donning VR glasses and body sensors. In front of them sat a (virtual) child. Using compassionate phrases provided by the researchers, the participant was told to comfort the child. The child responded to this kindness. In the next phase, the participant’s focus was shifted so that they were now looking out through the eyes of the child at the adult avatar they had just embodied. They listened to the kind words they had just spoken played back in their own voice. For many it was a remarkable and intense experience. (Chatfield, 2016)

You must be logged in to post a comment Login